The Literature Review

Entering the Scholarly Conversation

Imagine you are walking into a room where a lively and complex conversation has been going on for a long time. The participants are knowledgeable, passionate, and have been debating a topic from various angles, building on each other’s points, and challenging established ideas. You have a new thought you are eager to share, an observation you believe is important. But if you simply blurt it out without first listening to what has already been said, your contribution is likely to be ignored, dismissed as naive, or seen as a repetition of a point made long ago. To contribute meaningfully, you must first listen. You must understand the history of the conversation, identify the key speakers, grasp the major points of agreement and contention, and recognize what is currently being discussed.

This is the perfect metaphor for the research process. No research project is conducted in a vacuum. Every study is part of a larger, ongoing scholarly conversation that has been unfolding for years, sometimes decades, in the pages of academic journals, books, and conference papers. The literature review is the essential and disciplined act of listening to that conversation. For many students, the literature review is the most intimidating part of the research process. It can feel like a monumental and tedious task of finding, reading, and summarizing an endless number of articles. This chapter aims to reframe that task. A literature review is not a passive summary or an annotated bibliography; it is an active, critical, and persuasive argument. It is the intellectual labor of finding, evaluating, and synthesizing previous scholarship to build a compelling case for your research. It is how you demonstrate to your audience that you have done your homework, that you understand the existing landscape of knowledge, and that you have identified a genuine gap, a pressing contradiction, or an unanswered question that your proposed study is uniquely positioned to address.

Mastering the literature review is the process of earning the right to ask your question. It is the crucial step that transforms a personal interest into a legitimate scholarly inquiry. This chapter will demystify this process, providing a practical, step-by-step guide to navigating the academic landscape. We will cover how to strategically search for relevant sources, how to critically evaluate their quality, how to synthesize them into a coherent narrative, and how to structure that narrative to build a powerful rationale for your research. By the end of this chapter, you will see the literature review not as a hurdle to be overcome, but as the foundational act of scholarship that connects your work to the rich and dynamic conversation of your field.

The Purpose and Goals of a Literature Review

Before diving into the “how-to” of conducting a literature review, it is essential to have a clear understanding of why it is such a fundamental part of the research process. A well-executed literature review accomplishes several critical goals simultaneously, each of which strengthens the foundation of the proposed study.

Goal 1: To Situate Your Research in the Existing Dialogue

The primary purpose of the literature review is to share with the reader the results of other studies that are closely related to the one you are undertaking. This act of situating your work demonstrates that you are aware of the broader context and are not working in isolation. It shows how your study relates to the larger, ongoing dialogue in the literature, positioning your project as the next logical step in a chain of inquiry. By connecting your research to established theories and previous findings, you are building on the collective knowledge of your field, rather than starting from scratch.

Goal 2: To Justify the Need for Your Study by Identifying a “Gap”

Perhaps the most crucial function of the literature review is to provide a clear warrant or rationale for why your study is necessary. This is achieved by systematically identifying a “gap” in the existing body of work. This gap can take several forms:

A Topical Void: No one has studied this specific topic, this particular population, or this new communication technology before.

A Contradiction: Previous studies have produced conflicting or contradictory findings, and your study aims to resolve this inconsistency.

An Alternative Explanation: Existing theories provide one explanation for a phenomenon, but you believe an alternative perspective could be more insightful, and your study is designed to explore it.

By demonstrating this gap, the literature review answers the crucial “so what?” question. It persuades the reader that your study is not redundant but is essential for filling a hole in our collective understanding.

Goal 3: To Avoid “Reinventing the Wheel”

A thorough review of the literature ensures that you are not inadvertently proposing a study that has already been conducted. It is a frustrating but not uncommon experience for a novice researcher to develop what they believe is a brilliant and original idea, only to discover through a literature search that it was the subject of a dissertation ten years ago. The literature review is a due diligence process that saves you from wasting time and effort on a question that has already been adequately answered.

Goal 4: To Learn from the Methodological Successes and Failures of Others

Beyond the findings of previous studies, the literature review provides a wealth of information about the methods other researchers have used. By examining their work, you can learn about established measurement scales that are reliable and valid, successful sampling strategies for reaching specific populations, and innovative analytical techniques. Conversely, you can also learn from the limitations that other authors identify in their work. If previous studies have been criticized for using a particular methodology, you can design your study to avoid that same pitfall, thereby strengthening your contribution.

Goal 5: To Refine and Focus Your Research Question

The process of engaging with the literature is often what sharpens a broad interest into a precise and researchable question. You may start with a general interest in “social media and politics.” Still, through your reading, you might discover a specific debate about the role of visual memes in youth political engagement on Instagram. The literature provides the concepts, terminology, and theoretical frameworks that allow you to formulate a question that is not only interesting but also specific enough to be empirically investigated.

The Process of the Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide

The literature review can feel like a daunting task, but it becomes far more manageable when broken down into a series of logical and sequential steps. This process moves from broad exploration to focused synthesis, culminating in a written argument that serves as the introduction to your research proposal.

Step 1: Topic Identification and Keyword Generation

The process begins with a topic. As discussed in previous chapters, this should be an area of genuine interest that is also manageable in scope. The first practical step is to translate this topic into a set of keywords that will be used to search for relevant literature. This is a crucial brainstorming phase. Think about your core concepts and generate a list of synonyms and related terms for each. For example, if your topic is the effect of online news consumption on political polarization, your keywords might include:

Concept 1 (Online News): “online news,” “digital news,” “internet news,” “social media news,” “news websites,” “news aggregators”

Concept 2 (Political Polarization): “political polarization,” “partisan division,” “ideological extremity,” “affective polarization,” “political disagreement”

Having a rich list of keywords is essential because different authors may use different terminology to describe similar concepts. This initial list will evolve as you begin reading and discover the specific language used in the scholarly literature on your topic.

Step 2: The Search Process—Finding the Conversation

With your initial keywords in hand, you can begin the search for scholarly sources. The goal is to find the central, peer-reviewed literature that constitutes the core of the scholarly conversation on your topic.

Where to Look:

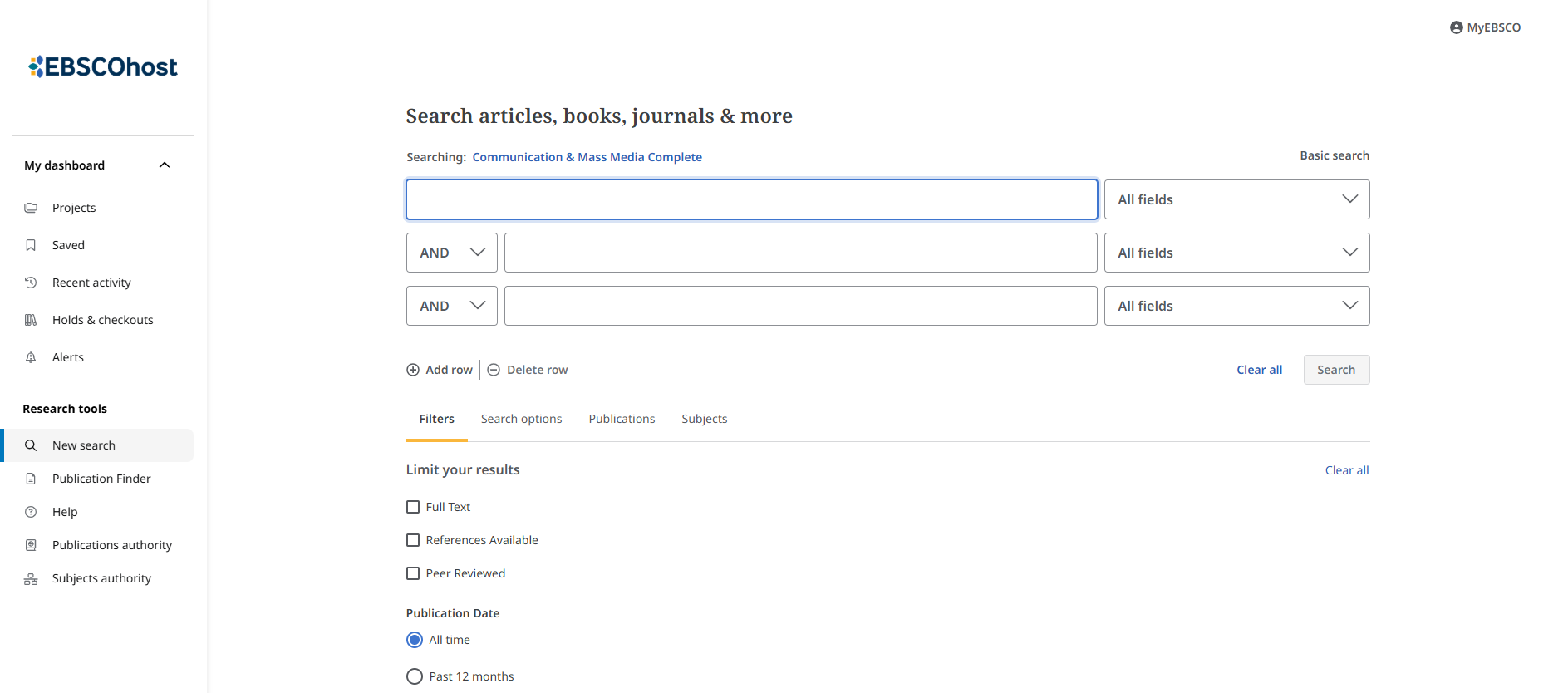

- Academic Databases: Your university library provides access to a host of academic databases. These are the primary tools for a literature review. For communication research, key databases include Communication & Mass Media Complete, PsycINFO, and SocINDEX. General-purpose academic search engines like Google Scholar are also incredibly powerful, especially for forward citation chaining. These databases are essential because they index peer-reviewed journal articles—the gold standard for scholarly research.

Books and Edited Volumes: While journal articles report the most current research, books and chapters in edited volumes often provide more comprehensive theoretical overviews or foundational summaries of a topic. Use your library’s catalog to search for relevant books.

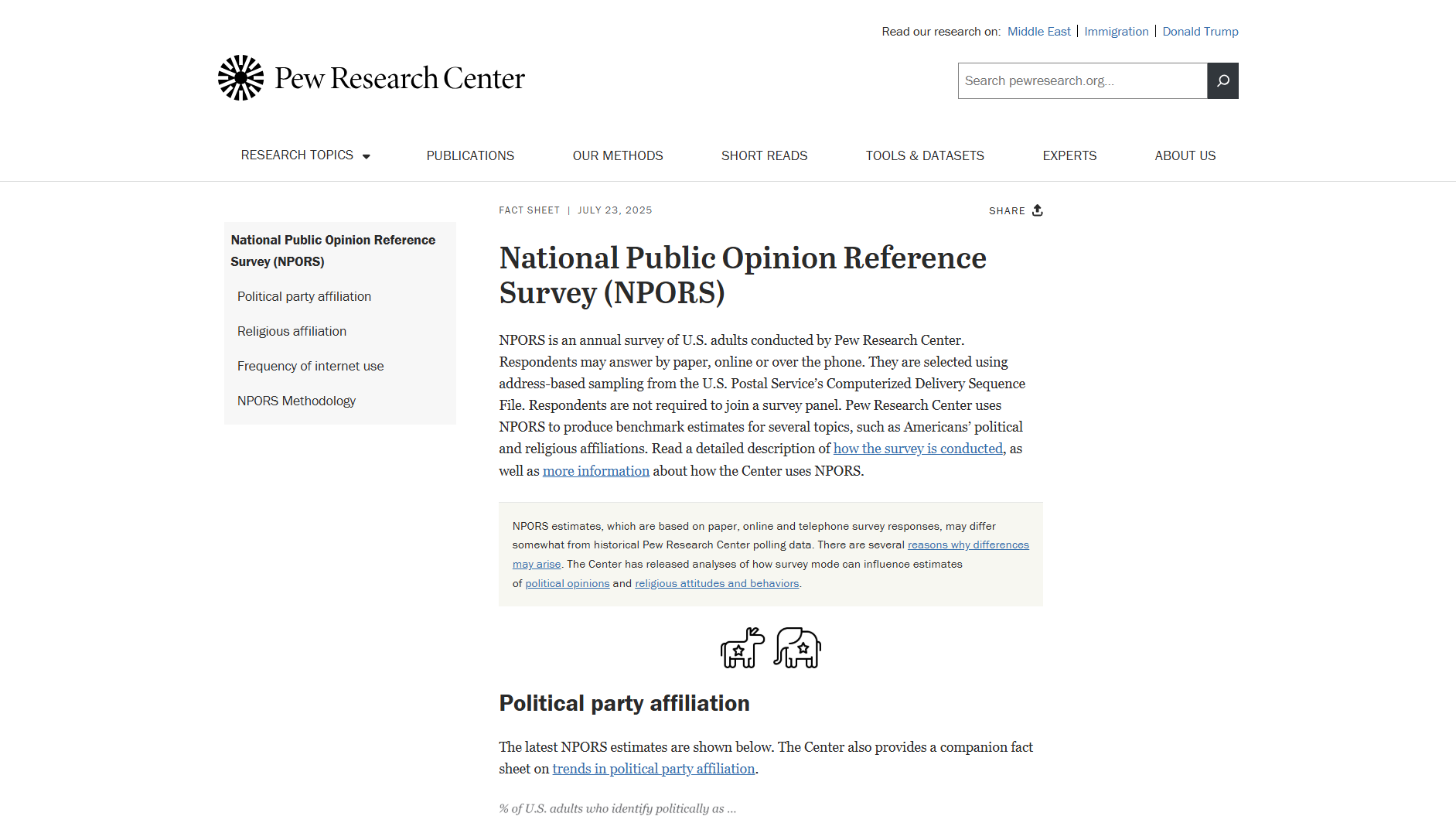

Government and Foundation Reports: For specific topics, particularly those related to public policy or applied research, reports from government agencies (e.g., the Pew Research Center, the U.S. Census Bureau) or major foundations can be valuable sources of data and context.

How to Search:

A strategic search is more effective than a scattershot one. Use a combination of techniques to ensure your search is comprehensive.

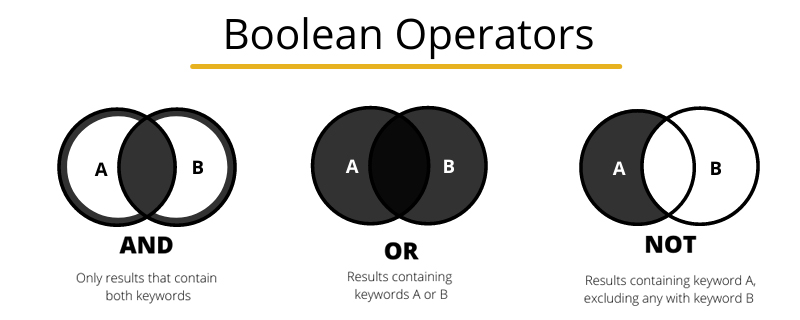

Keyword Searching with Boolean Operators: Begin by incorporating your keywords into the databases. Refine your searches using Boolean operators:

- AND narrows your search (e.g., “social media” AND “mental health”).

- OR broadens your search by including synonyms (e.g., “adolescents” OR “teenagers”).

- NOT excludes terms from your search (e.g., “social media” NOT “marketing”).

Citation Chaining: This is perhaps the most powerful search strategy. Once you find one or two highly relevant, “keystone” articles, you can use them to spiderweb out to the rest of the relevant literature.

Backward Chaining: Go to the reference list of your keystone article. Read through the titles of the works they cited. This is an excellent way to find the foundational and seminal studies upon which the current research is built.

Forward Chaining: Use a tool like Google Scholar. Find your keystone article and click on the “Cited by” link. This will show you a list of all the subsequent articles that have cited that work. This is the best way to bring your literature search up to the present day and see how the conversation has evolved.

Step 3: Evaluating and Selecting Sources

Your initial searches will likely yield a large number of potential sources. The next step is to critically evaluate them to determine which are most relevant and credible for your review.

The Hierarchy of Credibility: Prioritize sources based on their scholarly rigor. Peer-reviewed journal articles and scholarly books from academic presses are at the top of the hierarchy. Trade publications, popular magazines, newspaper articles, and general websites, while potentially useful for background context, are not typically considered primary sources for an academic literature review because they have not undergone the same rigorous review process.

Read the Abstract First: The abstract is a concise summary of an article’s purpose, methods, findings, and conclusions. Reading the abstract is the most efficient way to quickly determine if an article is relevant to your topic before you commit to reading the entire piece.

Criteria for Evaluation: As you skim abstracts and articles, ask yourself a series of questions:

Relevance: How directly does this study address my research question? Is it a central piece of the puzzle or only tangentially related?

Rigor: Is this an empirical study with a clearly described methodology? Is the journal reputable (You can look up a journal’s reputation and impact factor)? Is the research design sound?

Currency: When was this published? Is it still relevant, or have more recent studies superseded its findings? (Remember, however, that older, “foundational” studies can be just as critical as the latest research).

Step 4: Reading, Organizing, and Synthesizing

Once you have gathered a core set of relevant articles, the real intellectual work begins. This is the stage where you move from simply collecting sources to synthesizing them into a coherent argument.

Distinguish Between an Annotated Bibliography and a Literature Review: This is a critical distinction. An annotated bibliography is a list of sources, where each entry is followed by a paragraph that summarizes that single source. A literature review, by contrast, organizes sources thematically. Instead of discussing one article at a time, it synthesizes the findings from multiple articles to make a point about a particular theme or concept. Your goal is to write a literature review, not an annotated bibliography.

Active Reading and Note-Taking: As you read each article in depth, take systematic notes. For each study, identify the main research question, the theoretical framework, the methodology used (including the sample), the key findings, and the limitations identified by the authors.

Develop a Literature Map: A literature map is a visual tool for organizing the studies you have found. Begin by placing your central topic in the middle of a page. Then, create branches for the major themes or subtopics that you see emerging from the literature. Under each theme, list the key studies that address it. This visual organization helps you know the structure of the conversation and identify where the different pieces of research fit. It will become the outline for your written review.

The Act of Synthesis: Synthesis is the process of weaving together the findings from different studies to create a new, integrated understanding. Look for patterns across the studies. Where do different authors agree? Where do they disagree? How does a finding from one study build upon or challenge a finding from another? Your job is to narrate this conversation, summarizing the key points and highlighting the critical debates.

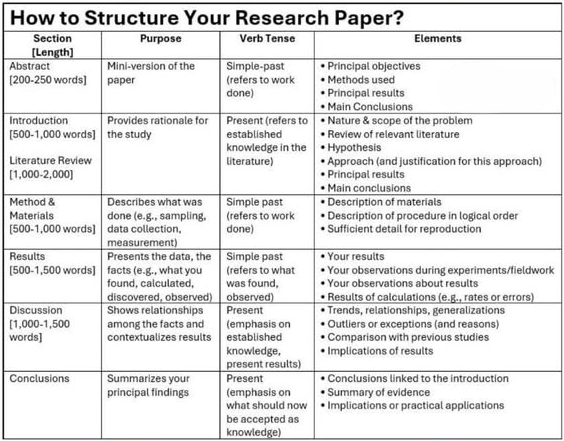

Step 5: Structuring and Writing the Review

With your literature map as your guide, you are ready to begin writing. A literature review should have a clear narrative structure with an introduction, a body, and a conclusion.

The Introduction: Begin by introducing the broad research topic and establishing its significance. Briefly state the scope of your review (what you will and will not be covering) and provide a roadmap for the reader, outlining the major themes you will discuss in the body of the review.

The Body (Thematic Organization): The body of the review should be organized thematically, following the structure of your literature map. Each section or major paragraph should focus on a specific theme, concept, or debate.

Start each section with a clear topic sentence that introduces the theme.

Within each section, synthesize the findings from multiple sources. Do not just summarize one study per paragraph. Instead, make a point and use evidence from several studies to support it (e.g., “Several studies have found a consistent link between X and Y.”).

Use transitions to create a smooth, logical flow from one theme to the next, building your argument step by step.

Acknowledge and discuss conflicting findings. A strong review does not ignore research that contradicts its central argument. Instead, it addresses these conflicts and attempts to explain them (e.g., “While most studies find X, Author D found Y, possibly due to a different methodology…”).

The Conclusion (The “Gap” and the Rationale): The entire review should build toward its conclusion. This is the most essential part of the literature review. First, briefly summarize the main takeaways from the literature you have reviewed. Then, pivot to the “so what.” Explicitly identify the gap, contradiction, or unanswered question that your review has uncovered. Finally, state the purpose of your own proposed study, clearly explaining how it will address this specific gap and, therefore, make a valuable and original contribution to the scholarly conversation.

The Concept of Saturation

How do you know when you are done searching for literature? The guiding principle is the concept of saturation. A literature review is considered saturated when your searches through databases and citation chains begin to yield little to no new information. You start seeing the same authors and the same articles cited repeatedly. The major themes and debates become clear, and new articles you find tend to fit neatly into the categories you have already developed in your literature map. Reaching saturation is a sign that you have conducted a comprehensive search and have a firm grasp of the universe of academic literature on your topic.

Conclusion: From Summary to Synthesis to Scholarly Contribution

The literature review is far more than a preliminary chore to be completed before the “real” research begins; it is a foundational and intellectually rigorous part of the research process itself. It is the mechanism through which you join a scholarly community. By systematically finding, evaluating, and synthesizing the work of others, you demonstrate your competence as a researcher and earn the credibility needed for your voice to be heard.

The literature review paves the journey from a vague interest to a focused research project. It transforms you from a passive consumer of knowledge into an active participant in its creation. It is in the act of reviewing the literature that you discover the gaps in our understanding and, in doing so, find the precise space where your unique contribution can be made. A well-crafted literature review is, therefore, not just a summary of what is known; it is a persuasive argument for what needs to be known next.

Journal Prompts

Reflect on the metaphor introduced at the beginning of the chapter: walking into a conversation that’s already underway. Have you ever had that experience in real life (in class, online, or at work)? What happened when you did—or didn’t—take the time to listen first? How does that scenario relate to the role of the literature review in research? Why is it important to understand what’s already been said before adding your ideas?

Think about a media-related topic that interests you (e.g., influencer culture, video game violence, media portrayals of mental health). Now imagine you are preparing to write a literature review on that topic. What kind of “gap” would you look for to justify a new study? Would it be a topical void, a contradiction, or an overlooked perspective? Why does that kind of gap matter in media research?

In your own words, explain the difference between an annotated bibliography and a proper literature review. Why is that difference significant? Reflect on a time when you had to summarize multiple sources for a paper or project. Did you organize those sources thematically, or treat each one individually? Looking ahead, how will your approach change when writing your literature review?