7 Selecting and Adapting Research Scales

This chapter aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the use and adaptation of research scales in mass communications. It will guide students through the process of selecting reliable and valid scales, adapting them to specific research needs, and doing so with ethical and legal considerations in mind. This will ensure that students are equipped to effectively measure complex constructs in mass communication research.

Overview of Research Scales in Mass Communications

Introduction to Widely Used Scale Types

Likert Scales

The Likert scale is extensively used for gauging attitudes and opinions in social media research. It typically presents respondents with a statement and asks them to express their level of agreement or disagreement on a five or seven-point scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” This format is particularly useful for measuring public opinion on various media topics, including reactions to social media posts, user sentiments about trending topics, or attitudes towards digital campaigns. The Likert scale’s simplicity and versatility make it a fundamental tool in social media analytics, enabling researchers to quantify subjective data like opinions and attitudes.

Semantic Differential Scales

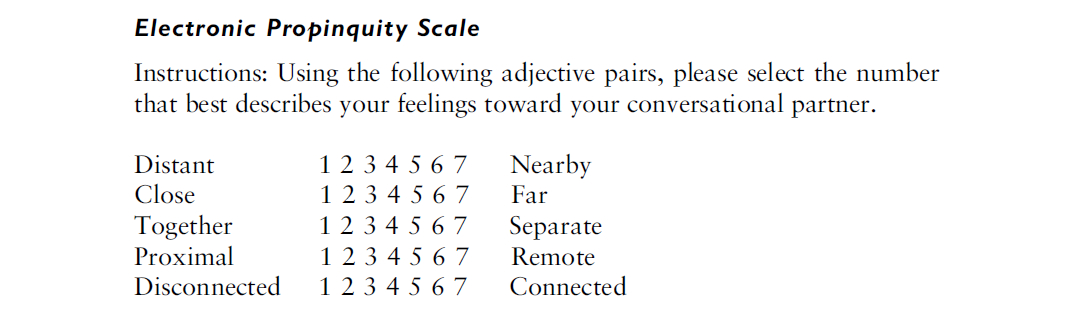

Semantic differential scales are utilized to assess the connotations associated with media messages, which is particularly relevant in the analysis of social media content. This scale asks respondents to rate a media message using a series of bipolar adjectives, such as “good-bad,” “positive-negative,” or “useful-useless.” In social media research, this scale can be employed to understand how users perceive the tone, sentiment, or general disposition of posts and messages. For instance, it can be used to evaluate public perception of a brand’s social media presence or to analyze the emotional tone of user-generated content.

Engagement Scales

Engagement scales are crucial in social media analytics for measuring how audiences interact with various platforms. These scales are designed to assess different dimensions of media usage and engagement, including the frequency and duration of use, the intensity of engagement, and the emotional connection users have with the content. In a social media context, such scales can help quantify user engagement with specific posts, profiles, or campaigns. They can provide insights into the effectiveness of social media strategies, user involvement levels, and the impact of social media content on audience behavior.

Each of these scales offers unique advantages for social media research. The Likert scale’s straightforward format is excellent for survey-based social media research, while the semantic differential scale provides nuanced insights into user perceptions. Engagement scales, on the other hand, are vital for understanding user interaction patterns on social media platforms. The selection and adaptation of these scales depend on the specific research objectives, the nature of the social media content being analyzed, and the characteristics of the target audience.

Specialized Scales in Mass Communications

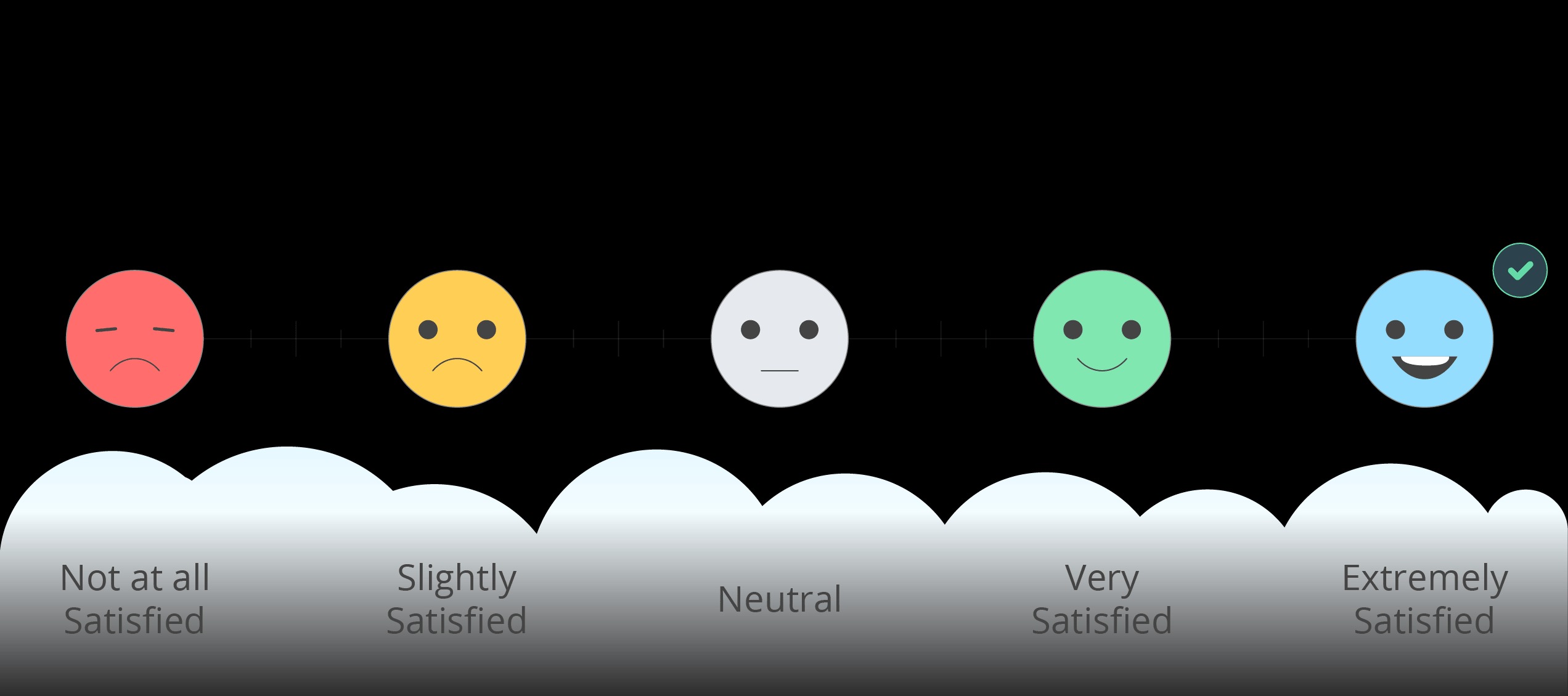

Audience Satisfaction Scale

The Audience Satisfaction Scale is designed to assess how viewers or readers feel about the media content they consume. This scale is especially significant in social media analytics, where understanding audience preferences and behavior is key to creating engaging content. By measuring satisfaction, researchers and content creators can gauge the success of their posts, videos, or articles in meeting audience expectations. This scale can involve various metrics, including content enjoyment, fulfillment of informational needs, and overall satisfaction with the media experience.

Media Credibility Scale

In an era where information is abundant and varied, the Media Credibility Scale plays a crucial role in determining which media outlets and content sources are perceived as trustworthy by the audience. This scale evaluates aspects like the perceived accuracy, bias, and reliability of different media sources. In social media analytics, this scale can be applied to measure how audiences perceive the credibility of news shared on social platforms, influencer endorsements, or branded content. Understanding these perceptions is vital for media outlets, marketers, and content creators aiming to build and maintain trust with their audience.

Advertising Effectiveness Scale

This scale is essential for evaluating the impact of advertising campaigns on social media. It measures how advertising influences audience perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. Key components of this scale may include audience recall of the advertisement, changes in attitudes towards the product or brand, and subsequent consumer actions, such as making a purchase or following the brand on social media. The Advertising Effectiveness Scale helps advertisers and marketers to quantify the return on investment of their campaigns and to refine their strategies for greater impact in future campaigns.

Each of these scales offers unique insights into different facets of mass communication in the digital age. By applying these scales in social media analytics, researchers and practitioners can gain a deeper understanding of audience dynamics, media credibility, and the effectiveness of advertising strategies, all of which are crucial in the rapidly evolving landscape of digital media.

Criteria for Selecting Appropriate Scales

Reliability and Validity Considerations

Defining Reliability and Validity

Reliability: This term refers to the consistency of a scale over time and across various contexts or samples. A reliable scale is one that yields similar results under consistent conditions. For instance, if a scale measuring audience engagement with a TV show provides consistent results across different audience groups and over multiple episodes, it is considered reliable.

Validity: Validity, conversely, pertains to the accuracy of the scale in measuring what it is intended to measure. This means the scale accurately assesses the specific concept or construct it’s supposed to evaluate. For instance, a valid scale for measuring social media influence should accurately assess influence, not just popularity.

Illustrating Concepts with Sourcebook Examples

Reliability Example: To illustrate reliability, consider a scale from the “Communication Research Measures” sourcebooks that measures media engagement. For it to be deemed reliable, the scale should consistently measure the level of engagement (such as time spent viewing, likes, and shares) across different studies, showing little variation in results under similar conditions.

Validity Example: As an example of validity, consider a scale designed to assess the credibility of news sources. This scale’s validity would be evidenced by its ability to accurately measure the perceived trustworthiness and accuracy of the news, not influenced by unrelated factors like the popularity of the news source or the medium through which the news is delivered.

In summary, the concepts of reliability and validity are crucial in the selection and adaptation of research scales in mass communications and media. Ensuring that a scale is both reliable and valid is key to producing meaningful and trustworthy results in any research study.

Evaluating Scales for Research

Assessing Reliability

Test-Retest Reliability: This method involves administering the same scale to the same group of people at two different points in time. A high correlation between the two sets of results indicates good test-retest reliability.

Inter-Rater Reliability: This assessment is crucial when the scale involves subjective judgments. It measures the extent to which different raters or observers give consistent estimates.

Internal Consistency: Often measured using Cronbach’s alpha, this method assesses whether the items on a scale are all measuring the same underlying attribute. A high Cronbach’s alpha value (typically above 0.7) suggests good internal consistency.

Determining Validity

Content Validity: This aspect checks whether the scale fully represents the concept it is intended to measure. It involves expert evaluation to ensure the scale covers the breadth of the concept.

Criterion-Related Validity: This form of validity is assessed by comparing the scale with another measure that is already accepted as valid. A high correlation with this criterion indicates good criterion-related validity.

Construct Validity: It involves evaluating whether the scale truly measures the theoretical construct it intends to measure. This is often achieved through factor analysis or correlating the scale with other variables that are theoretically related to the construct.

Practical Examples from Sourcebooks

The “Communication Research Measures” sourcebooks provide real-world examples of how various scales have been evaluated for reliability and validity. By carefully evaluating the reliability and validity of research scales, researchers in mass communications and media can ensure that their studies are built on solid, scientifically sound foundations. This process is crucial for the credibility and generalizability of their research findings.

- Argumentativeness Scale: Developed by Infante and Rancer (1982), this scale measures individuals’ tendencies to approach or avoid arguments. A study by Infante, Myers, and Buerkel (1994) titled “Argument and Verbal Aggression in Constructive and Destructive Family and Organizational Disagreements” utilized this scale to examine the relationship between argumentativeness and verbal aggression in different contexts.

- Communication Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ): Developed by Downs and Hazen (1977), the CSQ measures satisfaction with various aspects of organizational communication. A study by Hecht (1978) titled “The Measurement of Communication Satisfaction” used the CSQ to assess communication satisfaction within an organization and its relationship with job satisfaction.

- Interpersonal Communication Competence Scale: Developed by Rubin, Martin, and Bruning (1993), this scale assesses one’s perceived effectiveness in interpersonal communication. A study by Rubin, Martin, Bruning, and Powers (1993) titled “Test of a Model of Interpersonal Communication Competence” used this scale to analyze the factors contributing to effective interpersonal communication.

- Organizational Communication Scale: This scale focuses on communication patterns within organizations. A study by Goldhaber and Rogers (1979), “Audience Analysis for Communication Audit Research: A Question of Strategy,” used a version of this scale to evaluate communication strategies within organizations.

- Source Credibility Scale: Developed by McCroskey and Teven (1999), this scale measures perceived credibility of communication sources. A study by McCroskey, Richmond, and McCroskey (2006) titled “An Examination of the Relationship Between Teacher Credibility and Student Learning” used this scale to assess the impact of teacher credibility on student learning.

- Unwillingness-to-Communicate Scale: Developed by Burgoon (1976), this scale measures individuals’ general reluctance to communicate. A study by McCroskey and Richmond (1987), “Willingness to Communicate and Interpersonal Communication,” used this scale to explore the relationship between unwillingness to communicate and various aspects of interpersonal communication.

These studies exemplify the application of each scale in real-world research, demonstrating their utility in diverse areas of communication studies. Each of these scales has been instrumental in advancing our understanding of communication processes in different contexts.

References (in citation order)

- Infante, D. A., & Rancer, A. S. (1982). A conceptualization and measure of argumentativeness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 46(1), 72-80. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4601_13

- Infante, D. A., Myers, S. A., & Buerkel, R. A. (1994). Argument and verbal aggression in constructive and destructive family and organizational disagreements. Western Journal of Communication, 58(2), 73-84. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570319409374466

- Downs, C. W., & Hazen, M. D. (1977). A factor analytic study of communication satisfaction. Journal of Business Communication, 14(3), 63-73. https://doi.org/10.1177/002194367701400306

- Hecht, M. L. (1978). The conceptualization and measurement of interpersonal communication satisfaction. Human Communication Research, 4(3), 253-264. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1978.tb00614.x

- Rubin, R. B., Martin, M. M., & Bruning, S. S. (1993). Development of a measure of interpersonal communication competence. Communication Research Reports, 10(1), 33-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824099309359914

- Rubin, R. B., Martin, M. M., Bruning, S. S., & Powers, D. E. (1993). Test of a model of interpersonal communication competence. Communication Quarterly, 41(3), 210-220. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463379309369875

- Goldhaber, G. M., & Rogers, D. P. (1979). Auditing organizational communication systems: The ICA communication audit. Human Communication Research, 5(3), 226-233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1979.tb00633.x

- McCroskey, J. C., & Teven, J. J. (1999). Goodwill: A reexamination of the construct and its measurement. Communication Monographs, 66(1), 90-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759909376464

- McCroskey, J. C., Richmond, V. P., & McCroskey, L. L. (2006). Analysis and improvement of the measurement of interpersonal attraction and homophily. Communication Quarterly, 54(1), 1-31. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370500090355

- Burgoon, J. K. (1976). The unwillingness-to-communicate scale: Development and validation. Communication Monographs, 43(1), 60-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637757609375916

- McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (1987). Willingness to communicate and interpersonal communication. In J. C. McCroskey & J. A. Daly (Eds.), Personality and interpersonal communication (Vol. 6, pp. 129-156). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Cultural and Contextual Appropriateness

Importance of Contextual Relevance: It is essential to choose scales that align with the specific research question, target audience, and cultural context. The relevance and appropriateness of scales in relation to the demographic and cultural background of the study participants cannot be overstated. For instance, a scale developed in one cultural context may not be directly applicable in another due to differences in cultural norms, values, and communication styles. Ensuring that the scales used in research are culturally sensitive and contextually relevant is crucial for the accuracy and credibility of the study’s findings.

Adapting Scales for Cultural Relevance: Adapting scales to different cultural and contextual settings requires careful consideration to maintain their reliability and validity. This process often involves translating the scale into the local language, modifying scale items to reflect cultural nuances, and conducting pilot tests to ensure the adapted scale accurately captures the intended constructs in the new context. Such adaptations should be done thoughtfully to avoid losing the essence of what the scale is intended to measure.

Sourcebook Examples of Cultural Adaptation: The “Communication Research Measures” sourcebooks provide several examples of how scales have been successfully adapted for use in different cultural contexts. These examples can offer valuable insights into the process of adapting scales to ensure they remain effective and relevant across diverse settings. For instance, a scale measuring audience engagement with media might be adapted to different cultural contexts by altering the examples used in scale items to reflect local media consumption patterns and preferences.

These considerations highlight the importance of not only selecting technically sound scales but also ensuring that they are culturally and contextually appropriate for the research at hand. By doing so, researchers can enhance the validity and applicability of their findings across diverse populations and settings.

Adapting Existing Scales

Procedures for Scale Adaptation

Guidelines for Scale Modification

Identify the Need for Adaptation: Before modifying a scale, it’s crucial to understand why adaptation is needed. This could be driven by various factors such as changes in the media landscape, the introduction of new communication platforms, or the need to apply the scale in different cultural contexts. For instance, a scale developed to measure audience engagement on traditional media platforms may require adaptation to be applicable to emerging social media platforms.

Step-by-Step Adaptation Process:

- Review the Original Scale: Begin by thoroughly understanding the original scale’s purpose, structure, and how it has been applied in previous studies. This understanding is crucial to maintain the integrity of the scale during adaptation.

- Define Adaptation Goals: Clearly articulate the objectives of the adaptation. This could involve targeting a new demographic, measuring a different aspect of communication, or making the scale relevant to a new media platform.

- Modify Scale Items: Based on the adaptation goals, revise existing items or add new ones to the scale. It’s important to ensure that the language and content of the scale are relevant to the new context and that the scale items remain clear and understandable.

- Consult Experts: Get feedback from experts in the field. They can provide valuable insights on whether the modifications effectively capture the intended constructs and whether they are appropriate for the new context.

- Pretest the Adapted Scale: Conduct a pilot study using the adapted scale. This step is crucial to test the functionality of the scale in the new context and to identify any issues that need further revision.

Documenting the Process: Maintain a detailed record of all modifications made to the scale. This documentation should include the reasons for adaptation, the nature of the changes made, feedback from experts, and findings from the pilot test. Keeping a comprehensive record enhances the transparency of the research process and is valuable for future reference and replication of the study.

By following these guidelines, researchers can ensure that the adapted scale is not only technically sound but also tailored to the specific requirements of their study, thus enhancing the validity and relevance of their research findings in mass communications and media.

Maintaining Scale Integrity

Ensuring Reliability and Validity

In the process of adapting research scales for mass communications and media studies, it is crucial to maintain the integrity of the scale to ensure its effectiveness in measuring what it is intended to. One of the primary considerations in this regard is preserving both the reliability and validity of the scale post-adaptation. Reliability refers to the consistency of the scale, ensuring that it produces stable and consistent results over time and across different populations. Validity, on the other hand, assesses whether the scale accurately measures the concept it is intended to measure.

To ensure reliability, one commonly employed statistical method is Cronbach’s alpha. This coefficient measures internal consistency, indicating how closely related a set of items are as a group. A high Cronbach’s alpha value (typically above 0.7) suggests that the scale items are measuring the same underlying construct, thus ensuring reliability.

Regarding validity, particularly construct validity, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is frequently used. EFA helps in understanding how the various items of a scale relate to the underlying theoretical constructs. It assists in determining whether the items group together in a way that is consistent with the conceptual understanding of the construct being measured. This step is vital in confirming that the adapted scale measures the intended constructs and not some unrelated factors.

Pilot Testing

Pilot testing plays a pivotal role in the adaptation of research scales. Conducting a pilot study with a sample drawn from the target population is instrumental in testing the functionality and effectiveness of the adapted scale. This preliminary testing phase helps in identifying potential issues with the scale items, their wording, or the format of the scale.

During pilot testing, researchers collect data using the adapted scale and analyze this data to pinpoint any problems. For example, certain items might be consistently misinterpreted by respondents, or some questions might not be differentiating as expected among different response groups. The insights gained from pilot testing are invaluable for making informed decisions about the scale before its application in a full-scale study.

Iterative Refinement The feedback and data gathered from pilot testing necessitate an iterative process of refinement for the adapted scale. This refinement process may involve several alterations to the scale, including rewording, removing, or adding items. Rewording might be necessary to clarify the meaning of items or to make them more applicable to the new context or population. In some cases, items that do not contribute to the reliability or validity of the scale might be removed. Conversely, new items may be added to better capture aspects of the construct that were previously underrepresented or absent.

This iterative process is crucial as it allows researchers to fine-tune the scale, enhancing its reliability and validity in the context of its new application. Each round of refinement is typically followed by additional testing, either through further pilot studies or other validation techniques, to ensure that the changes have improved the scale’s performance. The end goal of this meticulous process is to develop a scale that is not only adapted to the new context but also maintains, if not enhances, its psychometric properties. This ensures that the scale remains a robust tool for measuring constructs within mass communications and media research.

Language and Cultural Considerations

Cultural Sensitivity and Relevance

When adapting research scales for use in mass communications and media studies across different cultural contexts, it is imperative to integrate cultural sensitivity and relevance into the adaptation process. Cultural norms, values, and communication styles vary significantly across different societies and communities. This diversity necessitates a careful consideration of these elements to ensure that the scale items are not only understandable but also culturally resonant and appropriate.

For instance, a scale developed in a Western context might include idiomatic expressions, scenarios, or references that are not applicable or meaningful in other cultural settings. Similarly, concepts that are readily accepted and understood in one culture might be unfamiliar, sensitive, or even offensive in another. Therefore, when adapting scales, it is crucial to review each item for cultural appropriateness. This may involve altering examples, scenarios, or even the framing of questions to align with the cultural context of the target population.

Language Adaptation

Language adaptation is a critical step when a research scale is to be used in a context where the original language of the scale differs from that of the target population. A straightforward translation of the scale items might not suffice, as linguistic nuances could alter the meaning or significance of an item. To address this, a rigorous process of translation and back-translation is often employed.

In this process, the scale is first translated from the original language to the target language by a proficient translator. Then, a different translator, unaware of the original wording, translates it back to the original language. This back-translation is then compared with the original version of the scale. Discrepancies between the original and back-translated versions indicate areas where the translation may not accurately capture the essence of the original items. This process helps in ensuring that the translated scale retains the conceptual and semantic integrity of the original.

Consulting with Local Experts

Collaboration with local experts is invaluable in the scale adaptation process, particularly in ensuring cultural appropriateness and linguistic accuracy. Local researchers or practitioners who are familiar with the target culture can provide insights into cultural nuances, sensitivities, and preferences that might not be apparent to outsiders. They can review the adapted scale items for cultural and contextual relevance, suggesting modifications where necessary.

These experts can also assist in interpreting the nuances of language and meaning in the context of the target culture. Their input is crucial in ensuring that the scale does not just translate words but also effectively communicates the intended concepts in a manner that is respectful and relevant to the cultural setting. By involving local experts, researchers can significantly enhance the validity and effectiveness of the adapted scale, ensuring it is a robust tool for gathering meaningful data in mass communications and media research across diverse cultural contexts.

Ethical and Legal Considerations

When adapting scales for research in mass communications, it’s essential to consider both ethical and legal aspects. These considerations ensure that the research remains credible, respectful, and legally compliant.

Ethical Issues in Scale Adaptation

Maintaining Original Intent

In the adaptation of research scales for mass communications and media studies, a critical ethical consideration is the maintenance of the original intent and purpose of the measurement tool. The core objective of any scale is to measure specific constructs or phenomena accurately. Altering the fundamental purpose or essence of a scale, whether intentionally or inadvertently, can lead to significant misinterpretation of results. Such deviations can compromise the integrity and validity of the research.

For example, if a scale originally designed to measure “media trust” is adapted in a way that shifts its focus to “media consumption habits,” the fundamental purpose of the scale is altered. This misalignment can lead to erroneous conclusions and impede the contribution of the research to the broader academic discourse. Therefore, it is imperative for researchers to critically assess each element of the scale during the adaptation process to ensure that the original intent remains intact.

Preventing Misinterpretation

Misinterpretation of scale items by respondents is a notable risk in scale adaptation, particularly when modifying items for different cultural or linguistic contexts. Clear and precise wording is essential to minimize the possibility of misinterpretation. It involves careful consideration of the language and phrasing of questions, ensuring they are direct, unambiguous, and free from cultural biases or assumptions.

For instance, idiomatic expressions or culturally specific references may not translate effectively across different cultural settings and could lead to confusion or misinterpretation. Researchers must critically evaluate each item to ensure that it conveys the intended meaning accurately and clearly in the new context. This scrutiny is essential for preserving the reliability and validity of the scale in its adapted form.

Informed Consent and Confidentiality

When adapting scales involves collecting new data, adherence to ethical research practices becomes paramount. This includes securing informed consent from all participants and maintaining the confidentiality of their responses. Informed consent ensures that participants are fully aware of the nature of the research, their role in it, the potential risks, and their rights, including the right to withdraw from the study at any point.

Confidentiality involves safeguarding the personal and sensitive information provided by participants. This includes measures to ensure that individual responses cannot be traced back to specific participants, thereby protecting their privacy. These ethical considerations are fundamental to conducting research that respects and upholds the rights and dignity of participants.

Cultural Sensitivity

Cultural sensitivity is a critical aspect of ethical scale adaptation, particularly when scales are being adapted for use in diverse cultural contexts. It is vital for researchers to ensure that the content of the scale is respectful and does not inadvertently perpetuate stereotypes, biases, or cultural insensitivities. This requires a nuanced understanding of the cultural norms, values, and sensitivities of the target population.

When adapting scales, researchers should avoid items that may be culturally offensive or insensitive. Collaboration with cultural experts or representatives from the target population can be invaluable in identifying and addressing potential issues. This approach not only enhances the cultural appropriateness of the scale but also contributes to the ethical conduct of research that respects and values the diversity of human experiences and perspectives.

Legal Aspects of Scale Use

Copyright and Intellectual Property

In the field of mass communications and media research, the use and adaptation of existing scales often intersect with legal considerations, particularly regarding copyright and intellectual property. Many scales, especially those that are widely recognized and used, are protected by copyright laws. Utilizing these scales without proper authorization can constitute a breach of copyright, which can have serious legal implications. This is particularly pertinent when the research is intended for publication or public dissemination.

For example, scales like the Uses and Gratifications Scale or the Media Dependency Scale, which are frequently employed in media studies, may be subject to copyright protection. Researchers intending to use or adapt such scales must first ensure they are not infringing on the intellectual property rights of the scale’s creators. This is not just a legal necessity but also an ethical imperative in academic research.

Obtaining Permissions

To legally use or adapt a protected scale, researchers must obtain permission from the copyright holder, which is often the publisher or the author of the original scale. This process typically involves reaching out to the relevant party with a detailed request that includes the nature of the research and the intended use of the scale.

The request for permission should clearly articulate how the scale will be used, whether it will be adapted or used as-is, and the scope of the intended research. Some copyright holders may grant permission readily, while others might require more detailed information or even charge a fee for the use of their scale.

Proper Citation

When a scale is used or adapted in research, proper citation of the original source is not just a matter of academic courtesy but also a legal obligation. Correct citation acknowledges the intellectual property of the scale’s creator and maintains the transparency and integrity of academic research.

Proper citation should include comprehensive details such as the original author(s) of the scale, the title of the work in which the scale was published, the publication year, and other relevant bibliographic information. This practice ensures that the original creators receive due credit for their work and allows other researchers to trace the scale’s origin and use in the academic context.

Documenting Permissions

Maintaining a record of all permissions granted for the use or adaptation of scales is a crucial step in the research process. This documentation should include details such as the date of permission, the extent of the permission granted (e.g., use as-is, adaptation, public dissemination), and any specific conditions or limitations set by the copyright holder.

Such records are particularly important for the publication process, as academic journals and publishers often require proof of permission for the use of copyrighted materials. Furthermore, keeping a thorough record of permissions aligns with ethical research standards, demonstrating a commitment to respecting legal and intellectual property rights in academic work.

By adhering to these ethical and legal considerations, researchers can ensure that their use and adaptation of scales in mass communications research are both responsible and compliant with standard research practices.