6 Designing Quantitative Research

6.1 Research Design

Experimental Designs

Experimental designs are a fundamental component of quantitative research in mass media. They offer powerful methods to test hypotheses and establish causal relationships between variables. These designs are beneficial for exploring how different types of media content influence audience behavior and perceptions. By manipulating independent variables and observing the effects on dependent variables, researchers can gain valuable insights into the dynamics of media influence.

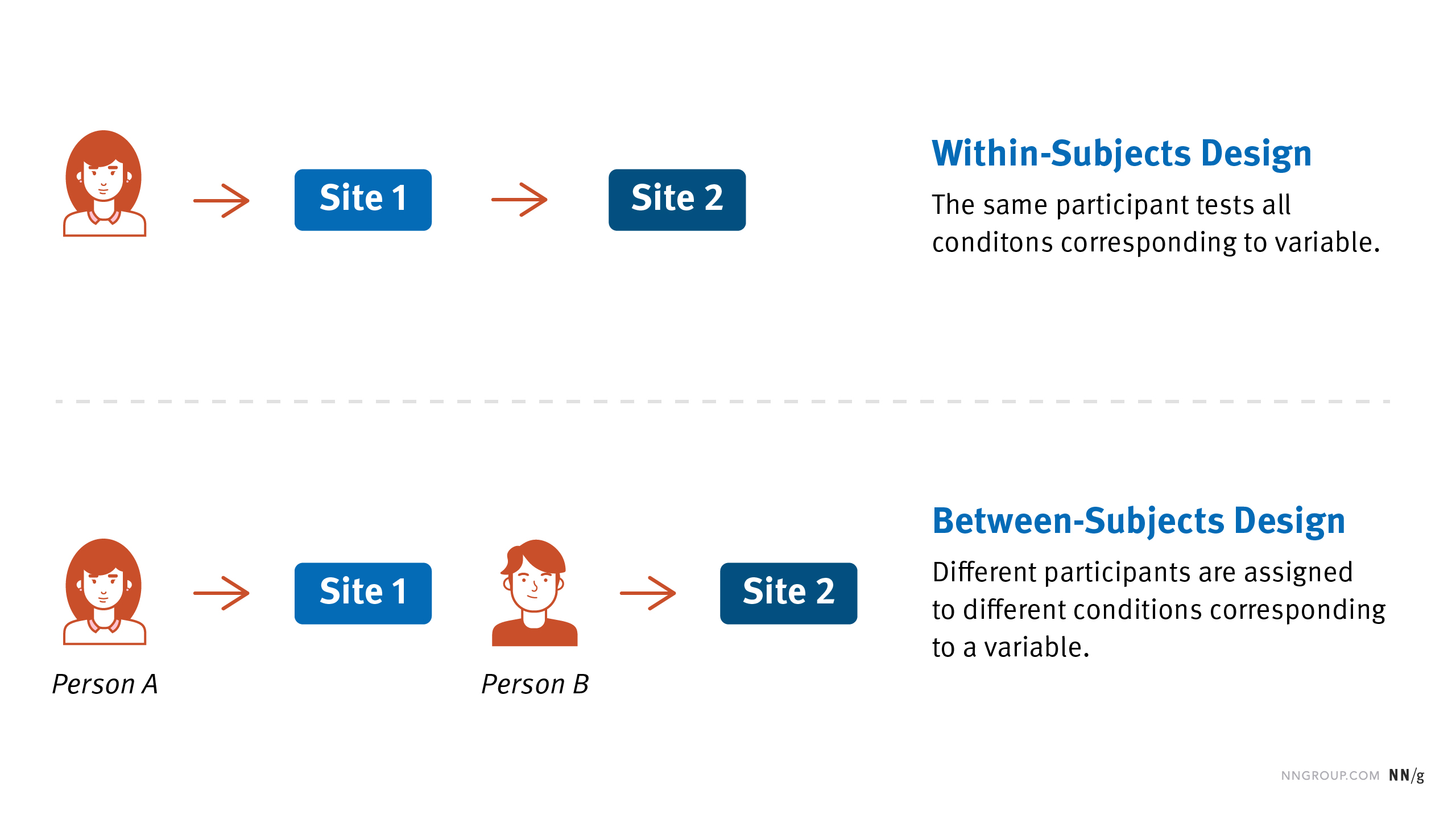

Between-Subjects Design

One of the most commonly employed experimental approaches is the between-subjects design. In this design, participants are divided into separate groups, each exposed to a different independent variable level. This structure allows for direct comparisons between groups to determine the effect of varying conditions. For example, one group might watch a news broadcast with a positive tone, while another group views the same one with a negative tone. By measuring differences in audience perceptions between these groups, researchers can assess how the tone of the broadcast affects reception.

The between-subjects design is particularly effective when the goal is to attribute observed effects directly to the independent variable, minimizing the influence of extraneous factors. Since each participant experiences only one condition, there is less risk of biases such as fatigue or learning effects that can occur with repeated exposures. However, ensuring that the groups are equivalent in all respects except for the experimental manipulation is crucial. Random assignment and matching are standard techniques used to achieve group equivalence, thereby enhancing the study’s internal validity.

Within-Subjects Design

In contrast, a within-subjects design involves exposing the same participants to all independent variable levels. This approach allows researchers to observe how changes in the independent variable affect the same individuals, effectively controlling for individual differences. For instance, participants might first watch a news broadcast with a positive tone and later view one with a negative tone, with their reactions measured after each exposure. By comparing responses within the same group, researchers can more precisely determine the impact of the variable.

While within-subjects designs offer the advantage of increased sensitivity to detecting effects, they can also introduce potential issues like order effects. The sequence in which conditions are presented might influence participants’ responses due to factors such as fatigue, practice, or carryover effects. To mitigate these concerns, researchers often employ counterbalancing techniques, varying the order of conditions across participants to distribute any order-related influences evenly.

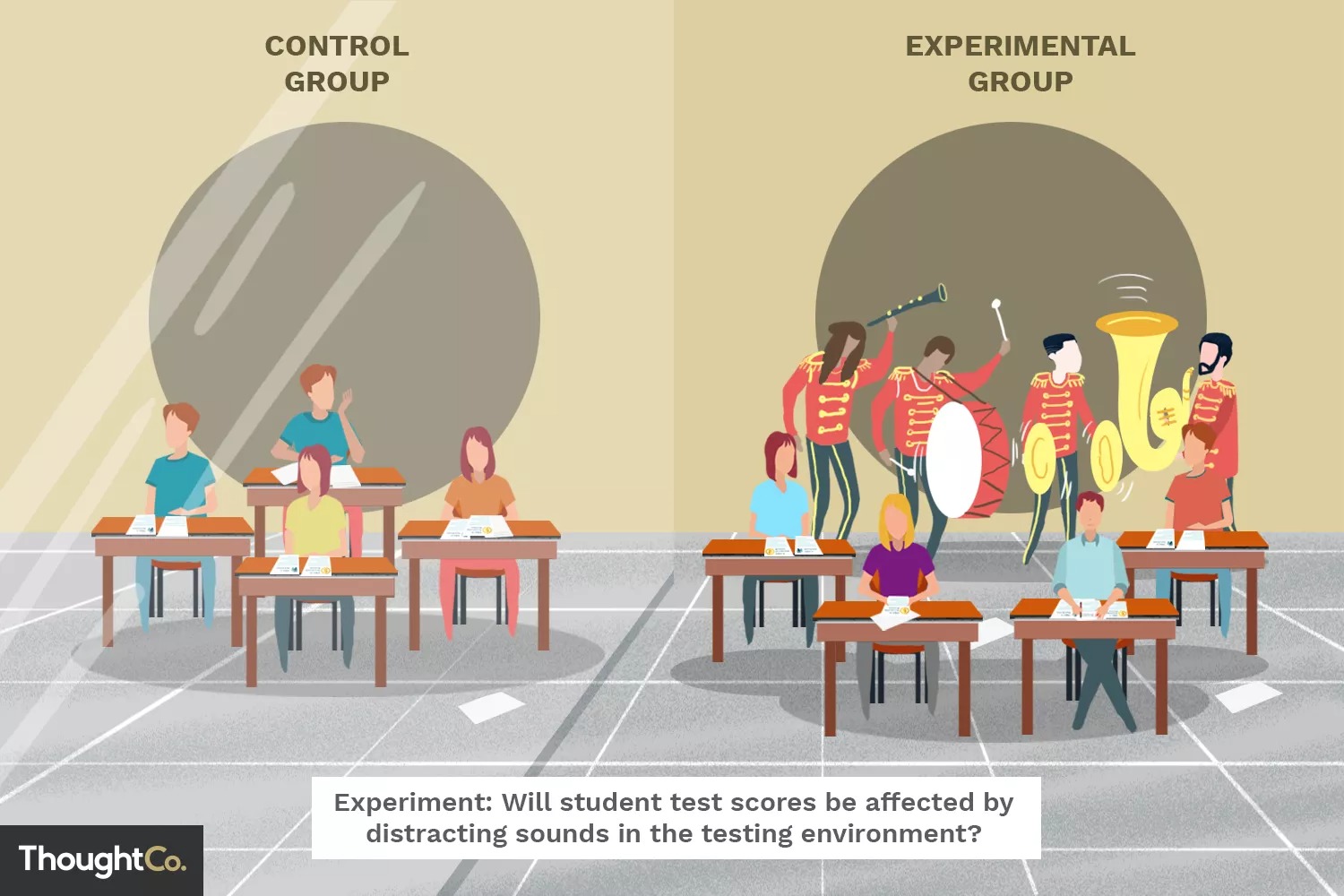

Control Groups

A critical element of any experimental design is including a control group. This group consists of participants who do not receive the experimental treatment and serves as a baseline for comparison. In mass media research, a control group might be exposed to neutral media content, while experimental groups encounter content with specific biases or manipulations. Researchers can determine whether the independent variable has a significant effect by comparing the control group’s responses to those of the experimental groups.

Control groups are essential for isolating the impact of the independent variable and ruling out alternative explanations for the findings. Without a control group, it becomes challenging to ascertain whether observed changes are due to the manipulation or other external factors. For example, if both the control and experimental groups exhibit similar changes in perception, this might indicate that factors unrelated to the media content are influencing the results.

Applying Experimental Designs in Mass Media Research

Understanding how to implement these experimental designs properly is crucial for conducting valid and reliable research in mass media. Through carefully structured experiments, researchers can explore questions such as:

- How does the framing of news stories influence audience attitudes toward social issues?

- What is the effect of exposure to violent media content on aggressive behavior?

- How do different advertising strategies impact consumer purchasing decisions?

By selecting the appropriate experimental design, researchers can tailor their studies to effectively address specific research questions. For instance, a between-subjects design might be ideal for comparing the effects of two distinct advertising campaigns on separate groups. Conversely, a within-subjects design could be more suitable for assessing changes in audience perceptions before and after exposure to a particular media message.

Conclusion

Mastering experimental designs empowers researchers to conduct rigorous investigations into the effects of media on audiences. By understanding the strengths and challenges of between-subjects and within-subjects designs, as well as the importance of control groups, researchers can enhance the validity and reliability of their studies. This foundational knowledge is essential for anyone engaged in mass communications research, providing the tools necessary to draw meaningful conclusions about the complex interplay between media content and audience response.

Non-Experimental Designs

In mass media research, not all studies permit experimental manipulation due to ethical, practical, or logistical constraints. In such cases, researchers rely on non-experimental designs to observe and analyze data as it naturally occurs. Two prevalent non-experimental approaches are cross-sectional designs and longitudinal designs. Understanding these methods is essential for conducting meaningful research when experiments are not feasible.

Cross-Sectional Designs

Cross-sectional designs involve observing a specific population at a single point in time. By collecting data simultaneously from different individuals, researchers can identify patterns, trends, and relationships between variables within a population. For example, surveying to assess public opinion on the influence of social media platforms at a particular moment provides a snapshot of current views and behaviors.

The primary advantage of cross-sectional designs is their efficiency. Data collection occurs once, making these studies relatively quick to complete and often less costly than other designs. They are handy for descriptive research aiming to understand the prevalence or distribution of a phenomenon within a population.

However, cross-sectional designs have limitations regarding causal inference. Since data is collected at one point, determining the directionality of relationships between variables or establishing cause-and-effect links is challenging. For instance, if a study finds that individuals who spend more time on social media report higher levels of anxiety, it cannot clarify whether social media use causes anxiety, anxiety leads to increased social media use, or if another factor influences both variables.

Longitudinal Designs

Longitudinal designs involve observing the same participants over an extended period. By tracking changes within the same group of individuals, researchers can more effectively study developments, trends, and potential causal relationships. For example, following a group of participants over several years to examine how prolonged exposure to certain media content influences their political attitudes allows researchers to see how variables evolve and how earlier experiences impact later outcomes.

Longitudinal designs are valuable for studying changes and developments over time. They provide insights into long-term effects and can help establish causality by demonstrating how one variable influences another across different periods. For instance, a longitudinal study might reveal that increased media exposure during adolescence leads to specific changes in political attitudes in adulthood, offering evidence of a causal relationship.

Despite their strengths, longitudinal studies present challenges. Participant attrition, or dropout, is a significant concern. Over time, some participants may leave the study due to loss of interest, relocation, or life changes, which can introduce bias if the remaining participants differ systematically from those who leave. Additionally, longitudinal research is more time-consuming and costly, requiring sustained resources and meticulous planning.

Applying Non-Experimental Designs in Mass Media Research

Understanding the advantages and limitations of cross-sectional and longitudinal designs is crucial for mass media researchers. These designs are often employed when experimental manipulation is not possible, but valuable insights are still needed.

Case Study—Cross-Sectional Design: A researcher conducts a nationwide survey to explore the relationship between social media usage and trust in traditional news outlets. By analyzing data collected at one point, the researcher identifies correlations and patterns that inform our understanding of media consumption behaviors.

Case Study—Longitudinal Design: This long-term study follows a group of teenagers over a decade to assess how early exposure to violent video games influences aggressive behavior into adulthood. By collecting data at multiple intervals, the study provides evidence of potential causal links between media exposure and behavioral outcomes.

Addressing challenges like participant dropout in longitudinal studies involves maintaining regular contact, offering incentives, and employing tracking methods to keep participants engaged. In cross-sectional studies, careful sampling and statistical controls help mitigate limitations related to causality.

Conclusion

Mastering both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs equips researchers with essential tools for conducting insightful and methodologically sound studies in mass media. While cross-sectional designs offer efficiency and are excellent for identifying current relationships and trends, longitudinal designs provide depth in understanding changes over time and potential causal links. By selecting the appropriate design for specific research questions and being mindful of each approach’s strengths and limitations, researchers enhance their findings’ validity and impact in the dynamic mass media research field.

Sampling Methods

The method used to select a sample significantly impacts the validity and generalizability of research findings in mass media studies. Sampling methods determine how participants are chosen from the larger population and are crucial for ensuring that a study accurately represents the intended group. Various sampling methods exist, each with its advantages and limitations. Understanding these methods helps researchers make informed decisions about study design and result interpretation.

Random Sampling

One of the most influential and widely used methods is random sampling. In this approach, participants are selected so that every member of the population has an equal chance of being chosen. Random sampling is considered the gold standard because it minimizes selection bias and enhances the generalizability of study results.

For example, suppose a researcher surveys viewers to understand their preferences for television programs. By randomly selecting viewers from a television network’s entire subscriber list, each subscriber—regardless of viewing habits—has an equal chance of inclusion. This randomness helps ensure the sample is representative of the larger population, allowing for more confident generalization of the findings.

Random sampling is particularly valuable when drawing conclusions that apply broadly to the entire population. However, careful planning and sometimes a larger sample size are required to reflect the population’s diversity truly. While random sampling reduces bias, it does not eliminate it; factors such as non-response can still introduce some bias.

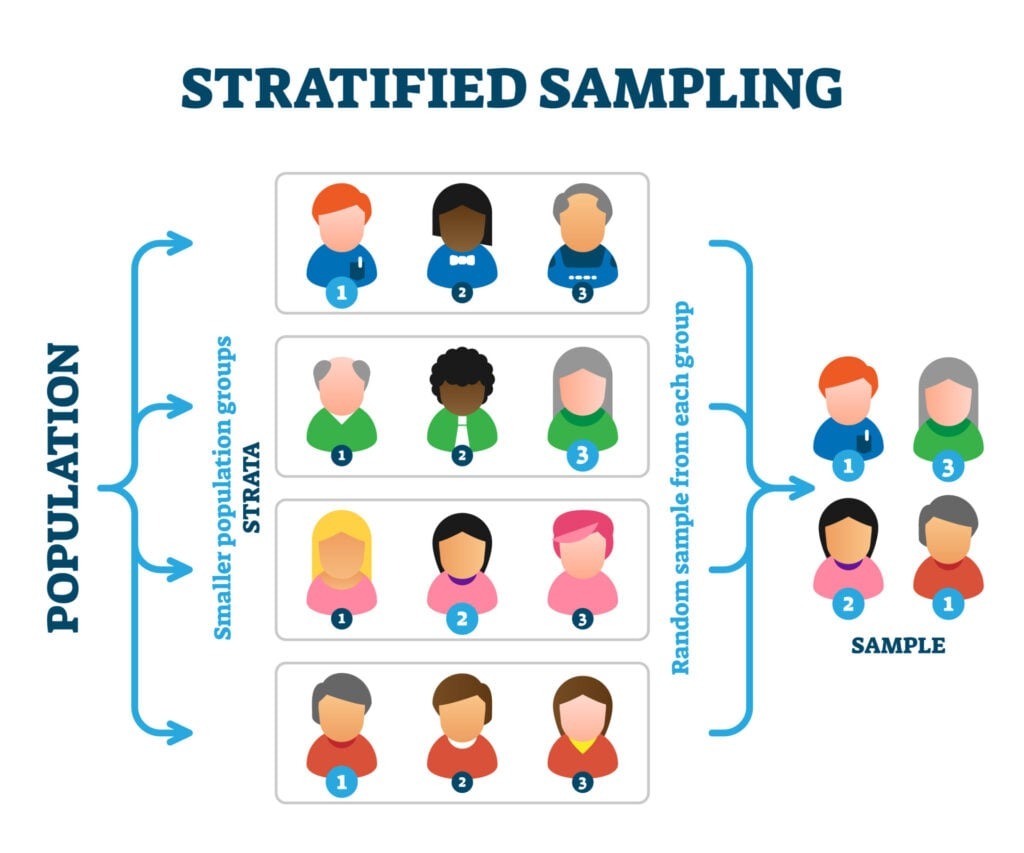

Stratified Sampling

Another critical method is stratified sampling, which involves dividing the population into distinct subgroups or strata and randomly sampling from each group. This approach ensures that each subgroup is adequately represented in the sample, especially when specific characteristics—such as age, gender, or income level—are essential for the research.

For instance, if studying media preferences across different age groups, a researcher might divide the population into age strata (e.g., 18–29, 30–49, 50 and above) and randomly select participants from each group. This method ensures that each age group is proportionally represented, allowing for more precise comparisons between groups.

Stratified sampling is particularly beneficial when the population is heterogeneous, meaning there are significant differences between subgroups. Ensuring proportional representation improves the accuracy of estimates and reduces sampling error. However, it requires detailed knowledge of the population and can be more complex to implement than simple random sampling.

Convenience Sampling

In contrast, convenience sampling involves selecting participants who are readily available and accessible to recruit. While practical and cost-effective, this method has significant limitations regarding representativeness and generalizability.

For example, convenience sampling is used to research media habits among college students by surveying students in one’s classes. Although straightforward, this sample may not represent all college students or the general population, potentially leading to biases in the findings.

Convenience sampling is often employed in exploratory research, pilot studies, or situations where other methods are not feasible. However, it is crucial to recognize its limitations: since the sample is not randomly selected, results may not be generalizable beyond the specific group studied. To mitigate some drawbacks, researchers can combine convenience sampling with other techniques, such as increasing the sample size or using quota sampling, to ensure some level of diversity within the sample.

Applying Sampling Methods in Mass Media Research

Understanding and correctly applying these sampling methods is vital in mass media research, where accurately capturing audience diversity is essential.

Random Sampling Case Study: A national survey assessing public trust in news media employs random sampling to include a wide range of demographic groups, enhancing the study’s generalizability.

Stratified Sampling Case Study: A study examining social media usage patterns divides participants into different age groups and samples each subgroup proportionally, ensuring meaningful comparisons across ages.

Convenience Sampling Case Study: A researcher might survey people at a local shopping mall for a preliminary study on reactions to a new advertising campaign. While offering immediate insights, the findings may not be generalizable to the broader population.

Conclusion

By mastering random, stratified, and convenience sampling methods, researchers are better equipped to select the most appropriate approach for their questions and understand each method’s implications for their findings. This knowledge is essential for conducting rigorous and credible research in mass media studies, where the sample’s representativeness directly affects the results’ validity.

6.2 Data Collection Techniques

Surveys and Questionnaires

Surveys and questionnaires are fundamental tools in mass media research, enabling efficient data collection from many participants. They allow researchers to gather information on attitudes, behaviors, preferences, and other variables of interest. The design of survey questions is critical to ensure that the data collected is accurate, meaningful, and truly reflective of respondents’ opinions. Understanding the different types of survey questions—such as Likert-type items, closed-ended and open-ended questions—is essential for designing effective surveys.

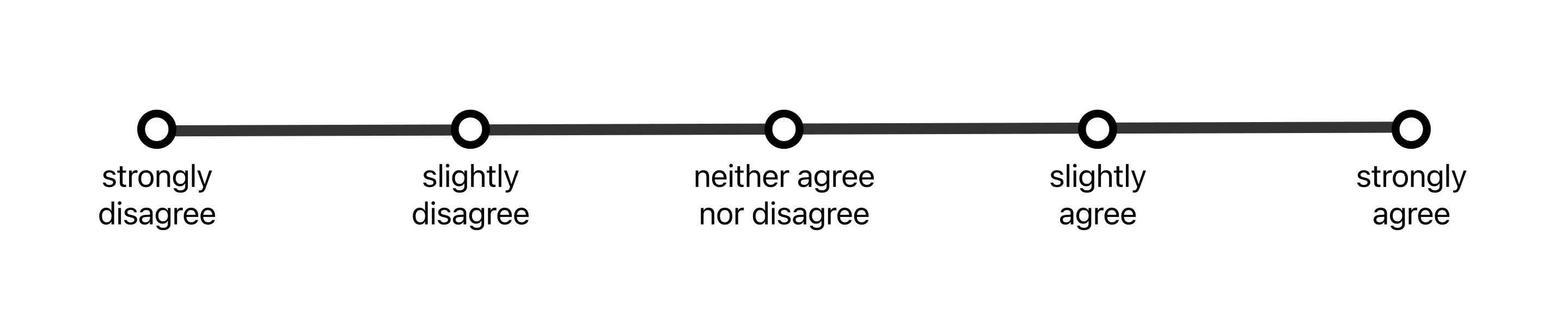

Likert-Type Items

One of the most widely used types of survey questions is the Likert-type item. This format presents a statement to which respondents indicate their level of agreement on a scale, typically ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” For example, a survey might ask respondents to rate their agreement with the statement, “Social media has a positive impact on society,” using a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Likert-type items are beneficial for measuring attitudes and opinions because they provide a clear, quantifiable way to capture the strength of respondents’ feelings on an issue.

The advantages of Likert-type items include their simplicity and standardization, which facilitate easy comparison across respondents. Because the scale is consistent across items, these questions can be used to create composite scores that reflect overall attitudes toward a topic. However, careful attention must be paid to the wording of the statements to avoid bias. Leading or ambiguous statements can skew responses, resulting in data that does not accurately reflect genuine opinions.

Closed-Ended Questions

Closed-ended questions provide respondents with a set of predefined responses to choose from. For example, a survey might ask, “How often do you use social media?” with response options like “Daily,” “Weekly,” “Monthly,” or “Never.” Closed-ended questions are highly efficient for collecting data because they are easy to answer and straightforward to analyze. They allow for quick comparisons and statistical analysis across different respondents.

The main advantage of closed-ended questions is their simplicity and ease of analysis. Since the responses are predefined, researchers can quickly categorize and quantify the data, making it easier to identify patterns and trends. However, a limitation is that they may constrain respondents’ answers, potentially losing nuanced information. If the predefined options do not fully capture respondents’ actual behaviors or opinions, the data collected may be inaccurate.

Open-Ended Questions

In contrast, open-ended questions allow respondents to answer in their own words, providing richer and more detailed data. For example, a survey might ask, “What do you think is the most significant impact of social media on society?” This type of question allows respondents to express their thoughts and opinions without being confined to predefined responses.

Open-ended questions are valuable because they can uncover insights that might be missed with closed-ended questions. They enable respondents to provide more nuanced and personal responses, revealing underlying attitudes, motivations, or concerns. However, the trade-off is that open-ended questions can be more challenging to analyze. The varied and complex nature of the responses requires careful coding and interpretation, which can be time-consuming.

Design Considerations

When designing surveys and questionnaires, it is crucial to consider the appropriate context for each type of question. Likert-type items are effective for measuring attitudes and opinions on a scale, closed-ended questions help collect quantifiable data efficiently, and open-ended questions are ideal for exploring complex issues in depth. Attention to question-wording, response options, and potential biases is essential to ensure that the data collected is accurate and meaningful.

Conclusion

By mastering Likert-type items and closed-ended and open-ended questions, researchers will be well-equipped to design surveys and questionnaires that effectively gather the necessary information. Understanding the appropriate context for each type of question and the implications for data analysis is essential for conducting rigorous and insightful research in mass communications.

Observation Methods

Observation methods are essential in mass media research, allowing researchers to study behaviors, interactions, and environments in their natural settings. Unlike surveys or experiments, which often involve some degree of control or intervention, observation methods enable data collection in an organic and unstructured way. Various observation techniques exist, each offering unique insights into human behavior. Understanding methods such as participant observation, complete observation, and direct observation enhances the ability to design and conduct research that captures the complexity of media interactions.

Participant Observation

In participant observation, the researcher actively engages in the environment or group being studied while simultaneously observing behaviors. This method is beneficial for studying social interactions and cultural practices, providing an insider’s perspective. For example, a researcher might join an online forum that discusses news events to observe how users interact and share information. By becoming a participant, the researcher experiences the group’s dynamics firsthand, gaining insights that might not be accessible through detached observation.

However, participant observation presents challenges, especially regarding ethical considerations and potential observer bias. The researcher’s presence and actions can influence the behavior of those being observed, a phenomenon known as the observer effect. Additionally, the researcher’s beliefs and experiences may color their observations, leading to bias in data collection. Maintaining a balance between engagement and objectivity is crucial, as is knowing how participation might affect the data.

Complete Observation

The complete observer method involves the researcher observing the environment without interacting or participating. This approach minimizes the researcher’s influence on the subjects, as participants are often unaware they are being observed. For instance, a researcher might observe interactions in a public place, such as a park or café, without engaging with the people being studied. By maintaining distance, the researcher can capture behaviors as they naturally occur, reducing the risk of altering the environment’s dynamics.

While the complete observer role reduces the observer effect, it also has limitations. One main drawback is the potential lack of depth in the data collected. Without engaging with participants, the researcher may miss the context or motivations behind certain behaviors. Ethical concerns can also arise, particularly regarding privacy and informed consent, especially in settings where participants are unaware of the observation.

Direct Observation

Direct observation involves systematically watching and recording behaviors or events as they naturally occur. Unlike participant observation, where the researcher engages with the environment, or complete observation, where the researcher remains detached, direct observation focuses on the structured recording of specific behaviors. For example, a researcher might observe and record the frequency of certain media consumption behaviors in a public space, such as how often people check their phones in a café.

Direct observation is helpful for studies requiring precise and quantifiable data on specific behaviors. It allows researchers to collect directly observable data, reducing reliance on self-reported information, which can be inaccurate or biased. However, maintaining consistency in recording behaviors and ensuring the observation process does not become intrusive are challenges that must be addressed.

Applying Observation Methods in Mass Media Research

Mastering these observation methods equips researchers to choose the most appropriate approach for their questions and conduct studies that capture the complexity of human behavior in media contexts. Each method offers unique insights and challenges:

Participant Observation Case Study: A researcher can gain insider perspectives on how information is shared and opinions are formed by joining an online community discussing current events.

Complete Observation Case Study: Observing interactions in a public setting without participation can reveal patterns in media consumption behaviors, such as how people engage with public digital displays.

Direct Observation Case Study: Systematically recording the frequency of smartphone use during social gatherings can provide quantifiable data on media habits.

Understanding when and how to use each method enhances the ability to gather meaningful and reliable data. Ethical considerations, such as informed consent and privacy, are paramount in observational research and must be carefully managed.

Conclusion

Observation methods are invaluable in mass media research for capturing the nuances of human behavior and media interactions. By effectively employing participant observation, complete observation, and direct observation, researchers can collect rich data that surveys or experiments might miss. This depth of understanding is essential for analyzing the complex ways in which media influences society and individual behaviors.

Content Analysis

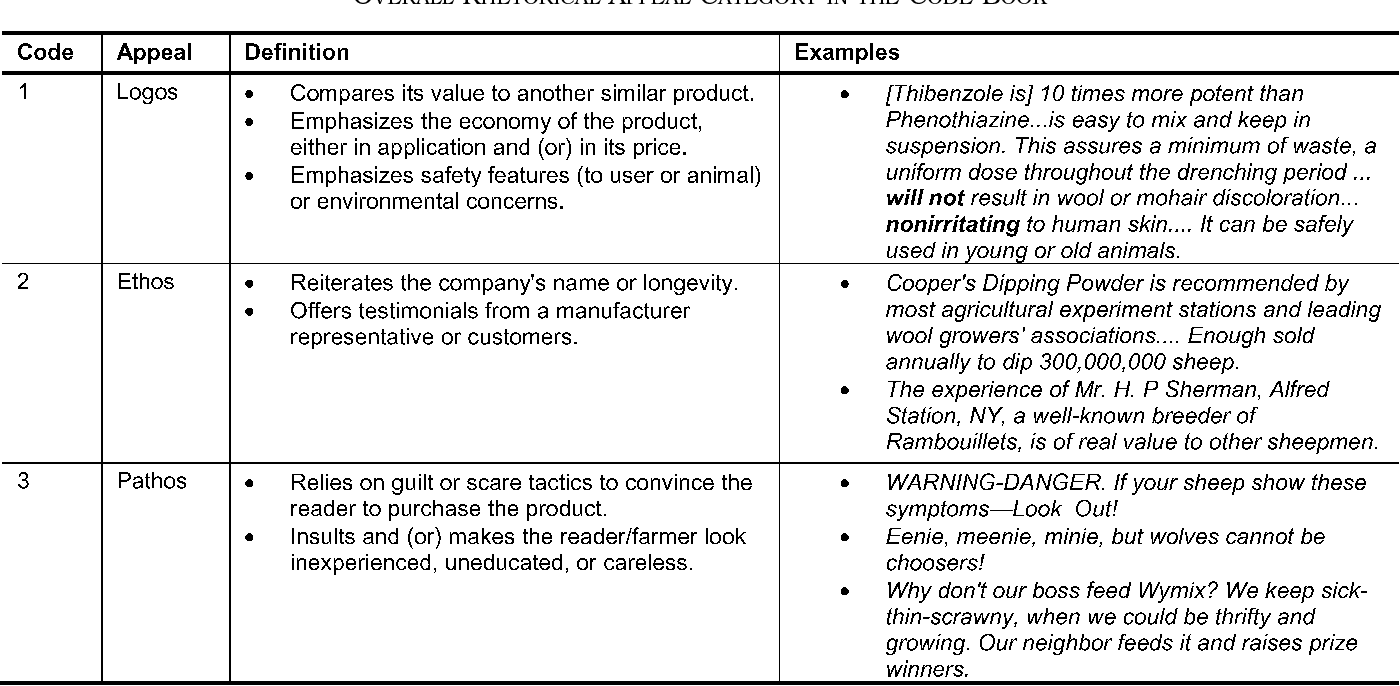

Content analysis is a systematic research method used to interpret and quantify media content by categorizing communication elements and examining the presence, meanings, and relationships of specific words, themes, or concepts. In mass media research, content analysis is invaluable for studying patterns, trends, and the influence of media messages on audiences. It enables researchers to uncover explicit and implicit messages conveyed through various media forms.

Manifest Content Analysis

Manifest content refers to the explicit, surface-level elements of media content that are directly observable and quantifiable. This includes the frequency of specific words, phrases, images, or other tangible components within a text or media piece. For example, a researcher might conduct a manifest content analysis to count how often the term “climate change” appears in newspaper articles over a certain period. By quantifying these occurrences, researchers can identify trends in topic coverage or the prominence of specific terms in the media.

The advantages of manifest content analysis lie in its objectivity and replicability. Since it focuses on observable data, the results are less subject to researcher bias and can be easily compared across different studies. However, while manifest content analysis effectively tells us what is present in the media, it does not delve into the deeper meanings or implications behind the content. For instance, knowing that “climate change” is frequently mentioned does not reveal whether the coverage is positive, negative, or neutral or what underlying messages are being conveyed.

Researchers often examine various media forms, such as newspapers, television broadcasts, and social media posts, to illustrate the application of manifest content analysis. By coding manifest content—such as counting keywords or categorizing images—they can systematically analyze media content. Clear coding guidelines are essential to ensure consistency and accuracy across the analysis.

Latent Content Analysis

In contrast, latent content refers to the underlying meanings, themes, or messages embedded within media content that are not immediately apparent. Latent content analysis goes beyond the surface to explore deeper significance, such as tone, bias, or ideological perspectives. For example, when analyzing a news article on political events, a researcher might examine whether the coverage subtly favors one political party over another or presents events positively or negatively.

Identifying and interpreting latent content is more complex and involves subjective judgment and interpretation. Different researchers might interpret the same content differently, leading to variability in findings. Therefore, latent content analysis often requires a nuanced approach and a thorough understanding of the context in which the content was produced and consumed.

The complexities of latent content analysis can be explored through case studies, where researchers analyze media samples to uncover hidden themes or biases. Engaging in group analyses to identify latent themes can highlight the subjectivity involved and the critical thinking required to conduct such analysis effectively.

The Coding Process

The process of coding is central to both manifest and latent content analysis. Coding involves categorizing and tagging content to identify patterns, themes, or trends within qualitative data. It allows researchers to systematically organize and interpret large amounts of data, making it easier to draw meaningful conclusions.

Developing a coding scheme is a critical step in content analysis. A well-defined coding scheme should be clear, consistent, and applicable across texts or media samples. For instance, researchers might develop codes to categorize media content as “informative,” “persuasive,” or “entertainment.” Applying this coding scheme to a sample of media texts enables analysis of the prevalence and distribution of these content types across platforms or periods.

Achieving inter-coder reliability is essential to ensure the validity of findings. This means that multiple researchers independently coding the same content should reach similar conclusions. Consistency in coding reduces bias and increases the credibility of the analysis.

Applying Content Analysis in Mass Media Research

By mastering manifest and latent content analysis techniques, researchers can conduct rigorous and insightful examinations of media content. These skills allow for uncovering both visible and hidden messages within the media, contributing to a deeper understanding of how media shapes and reflects societal values, beliefs, and behaviors.

For example, content analysis can be used to study:

- Gender Representation: Examining how different genders are portrayed in advertising to identify stereotypes or biases.

- Political Framing: Analyzing news coverage to see how political issues are presented and which narratives are promoted.

- Cultural Trends: Tracking the prevalence of specific themes or topics in social media to understand shifting public interests.

- Media Influence: Investigating how frequently particular health messages appear in media and their potential impact on public behavior.

By systematically analyzing media content, researchers can identify patterns and trends that inform our understanding of the media’s role in society.

Conclusion

Content analysis is a powerful method in mass media research for systematically examining media content. Whether focusing on explicit elements through manifest content analysis or exploring deeper meanings through latent content analysis, this method enables researchers to decode the complex messages conveyed by the media. The coding process is central to organizing and interpreting data effectively, and developing a reliable coding scheme is crucial for producing valid and meaningful results.

Understanding and applying content analysis equips researchers with the tools to critically assess media content, providing valuable insights into how media influences and reflects the world. These skills are essential for conducting thorough and impactful research in mass communications.